Covered Call Options Strategy: Beginner’s Guide

The covered call is an income-generating, high-probability strategy with limited reward. It slightly reduces downside risk but caps your upside if the stock rallies.

Covered calls are market-neutral to mildly bullish trades that generate income when the stock stays flat or rises modestly. Traders use them to collect premium while holding stock.

Highlights

- Risk: Significant downside risk. If the stock drops sharply, the premium collected offers only limited protection.

- Reward: Limited to the premium received plus any stock gains up to the strike price.

- Outlook: Best suited for neutral to moderately bullish expectations.

- Edge: Elevated implied volatility improves premium collected and lowers breakeven.

- Assignment Risk: Increases when the call is deep in the money and expiration is near.

Covered Call: Trade Construction

The covered call consists of two components:

- Purchasing 100 shares of stock

- Selling 1 call option

You can enter a covered call in one trade or sell calls against an existing long stock position. If you choose the latter, make sure to buy the stock first. If you sell the call before buying the stock, you'll face significant margin requirements and will be temporarily exposed to substantial risk.

Typically, the call sold is out of the money, which reduces the odds of the option being assigned. More on this later.

Outlook: When to Trade Covered Calls

The covered call is a multi-faceted trade. The ideal outlook for this strategy is when you don’t expect the stock to rally significantly by the option’s expiration date.

Here are a few different circumstances where selling a call against long stock may make sense:

- Income Generation: The covered call is a great way to generate income on a stock (as long as you don't get called out).

- Risk Reduction: The covered call is great for minor downside protection. Selling the call helps reduce the stock's cost basis.

- Planned Future Stock Sale: If you plan to sell your stock in the future when the stock reaches a certain price, selling a covered call lets you collect option premiums while you wait.

If you’re new to options trading, it will help to understand how short call options work before continuing.

Short Call Payoff Profile

Because the covered call involves both stock and options, its payoff profile is dynamic. Let’s take a look the three difference outcomes of this trade:

Max Profit Zone

Here's the max profit area for this strategy:

.png)

When you sell a call against stock you already own, your maximum profit is capped at the premium you collect plus any stock gains up to the strike price.

Max Profit = (Call Strike – Stock Purchase Price) + Premium Collected

Let’s say you own 100 shares of XYZ at $85 and sell the 90 strike call for $1.00 ($100 total). Here’s the setup:

- Stock Price: $85

- Call Strike Price: $90

- Premium Collected: $1.00 ($100 total)

- Max Profit: $600 (stock gain of $5/share + $1.00 premium)

If XYZ is trading above $90 on expiration, the shares get called away. You keep the $5 gain on the stock and the $1 premium — for a total profit of $600. If XYZ rallies above this point, you won’t make any additional profit, as the short call offsets gains from the long stock. Additionally, assignment odds are high in this zone.

Max Loss Zone

The real risk on a covered call comes on the stock. If the stock falls a lot, the premium collected helps offset this a little — but not much.

Max Loss = Stock Purchase Price – Premium Collected

Let’s say XYZ falls from $85 to $60 by expiration. Here’s the setup:

- Stock Price: $85 → $60

- Premium Collected: $1.00 ($100 total)

- Loss on Stock: $25/share → $2,500

- Offset by Premium: $100

- Max Loss: $2,500 – $100 = $2,400

That’s a steep loss, especially considering the most you could’ve made was just $600. Covered calls don’t do much to protect your downside.

Breakeven

To break even on a covered call, the premium collected must offset a drop in the stock.

Breakeven = Stock Purchase Price – Premium Collected

Using our example:

- Stock Purchase Price: $85

- Premium Collected: $1.00 ($100 total)

- Breakeven: $85 – $1.00 = $84.00

If XYZ is trading at $84.00 on expiration, the $1.00 premium cancels out the $1.00 loss on the stock — so you break even. Below that, you’re losing money.

Trade Example: Covered Call on SMH

In this real-world trade, we’re selling a 5% out of the money (OTM) call on SMH (VanEck Semiconductor ETF) with 37 days to expiration (DTE).

We picked SMH for a few good reasons:

- Broad-based semiconductors exposure

- Plenty of option liquidity

- Numerous strike prices and expirations

Let’s head to the TradingBlock platform to see the details of our trade:

Why I Chose This 5% OTM Call

I went with the $192 strike, which sits about 5% above our purchase price of $183.10. I also choose the 37-day mark because this is when time decay really picks up.

- Premium collected: $9.50, or $950 total — a solid credit for a 37-day call

- Time decay works for us — theta of -0.22 means we steadily earn as time passes

- Still gives us upside — we get another 5% room for growth before the call caps us

When determining the cost of a covered call, simply subtract the premium collected from the stock purchase price.

Therefore, this trade will cost us $17,360 ($183.10 × 100 shares – $950 premium).

Trade Details

Here are the trade details. Bear in mind the best-case scenario here is that SMH finishes just below our $192 strike at expiration because we keep the full premium and hold onto the shares

- Position: Long 100 shares SMH + Short 1 Call Option

- Stock Purchase Price: $183.10

- Strike Price: $192

- Premium Collected: $9.50 ($950 total)

- Net Trade Cost: $17,360 ($183.10 x 100 - $950)

- Expiration: 37 DTE

- Breakeven: $173.60 (stock minus premium)

SMH Covered Call: Positive Outcome

Let’s fast-forward 37 days to expiration. SMH had a solid run but stayed below our $192 strike price, meaning the call expired worthless and we kept the full premium.

Here’s how the trade played out:

- Expiration: 37 days → 0

- Strike Price: $192

- Stock Price: $183.10 → $190 📈

- Option Price: $9.50 → $0.00 📉

- Premium Kept: $950

- Net Trade Cost: $17,360

- Total Value at Expiration: $19,000

- Net Profit: $1,640 ($950 premium + $690 stock gain)

.png)

In this nearly perfect trade outcome, the stock closed at $190. Since it closed below the strike price, we didn’t miss out on any stock price appreciation. Additionally, we kept the full premium of 9.50 ($950) from the option we sold.

Notice how the time decay accelerates in the final days. We’ll discuss this time decay later in more detail.

✅ We kept the shares, banked the $950 premium, and made $690 on the stock — $1,640 profit in just over a month.

SMH Covered Call: Less Ideal Outcome

Let’s fast-forward to expiration. SMH surged and closed at $210, well above our $192 strike. The call finished deep in the money, and the position was likely assigned just before expiration, meaning our shares were sold at $192.

Here’s how the trade played out (assumed we were not assigned):

- Expiration: 37 days → 0

- Strike Price: $192

- Stock Price: $183.10 → $210 📈

- Option Price: $9.50 → $18.00 📈

- Premium Collected: $950

- Net Trade Cost: $17,360

- Total Value at Expiration: $19,200 (assignment at $192 + $950 premium)

- Net Profit: $1,840 ($950 premium + $890 stock gain)

.png)

This outcome reaches the maximum profit for our covered call. Still a win — but not without limits.

Once SMH crosses our $192 strike plus premium collected, the covered call value flattens out. Even as the stock keeps running, our return doesn’t budge — we’re capped at:

Max profit = ($192 – $183.10) + $9.50 = $18.40 per share, or $1,840 total

In reality, this trade probably would have been assigned around 2–3 days before expiration once the call was deep in the money and the time value mainly had burned off.

✅ We reached max profit — but left nearly $1,800 in stock gains behind by selling the call

Short Call: Strike and Expiration Selection

There are thousands of strike prices across dozens of expiration dates on stocks with lofty valuations. So why did I choose to sell the specific option I did on SMH? It wasn’t guesswork.

Let’s break down the key criteria you should review before picking the short call for your covered call position.

Short Call Strike Selection

Choose a strike that’s far enough OTM to allow for stock appreciation but close enough to offer a meaningful credit.

Look for a delta in the 0.30 to 0.50 range—high enough to collect a premium, but less likely to be in the money at expiration. If delta’s higher than usual, check the volatility—it may be inflating the number.

Expiration Date

Somewhere between 30–45 days is often ideal. If you choose an expiration further out, you’ll be waiting awhile for time decay (theta) to kick in on your short call.

Theta (Time Decay)

This is your friend when selling calls. But you want time decay to be worth the risk. A high theta with a high IV is often ideal—more decay + a bigger premium.

Theta’s of -0.20 to -0.30 work great for covered calls.

Implied Volatility (IV)

Higher IV means more premium. But be careful—elevated IV often comes with more risk. If volatility is temporary (news events, macro jitters), it might be worth selling into it. Just know what you’re signing up for.

Premium Collected

Ultimately, you want to collect a credit that justifies the risk and time. Make sure your max profit is worth capping the stock’s upside for that period.

Margin Requirements

The premium collected slightly reduces your cost basis, making the position marginally more efficient.

Let’s say ABC is trading at $100. You want to put on a covered call position, so you:

- Buy 100 shares at $100 = $10,000

- Sell one OTM call at the 105 strike for $0.50 = $50 premium collected

- Net outlay = $9,950 (your cost basis drops to $99.50/share)

That $0.50 premium comes straight off your cost basis—so your net outlay is $99.50 per share, or $9,950 total for 100 shares.

Covered Call Risks

The covered call is one of the few risk-averse options trades out there—but there are still a few things traders should watch out for.

Price Risk

With covered calls, the risk is all on the stock side. The short call slightly reduces your cost basis—but not by very much it’s not much.

Let’s say you own 100 shares of XYZ at $100 and sold a call for $1:

- XYZ collapses to $70 at expiration

- You keep the $1 premium

- You're still down $29/share → $2,900

- That $100 credit barely makes a dent

Covered calls help in sideways or mildly down markets—but if the underlying asset falls hard and fast, the call won’t mitigate much risk at all.

Early Assignment Risk

Assignment risk intensifies as expiration approaches. Most sufficiently in the money call options are assigned before expiration—especially when there’s little time value left.

This is because, by the last few days, most of the extrinsic value is gone, leaving the long call holder with little incentive to keep holding the option. Exercising early lets them lock in the intrinsic value instead.

📖 Intrinsic vs Extrinsic Value in Options

Dividend Risk

If your stock pays a dividend, you also run the risk of early assignment. This is only true for short calls that are in the money when the ex-dividend date approaches. Since long call don’t pay dividends, the long party will exercise their right to acquire the stock, and you’ll be assigned, thereby making you short 100 shares of stock and making you position neutral.

Liquidity Risk

.png)

Before placing any options trade, ensure adequate liquidity in the underlying assets options chain. Here’s what to look for:

- Bid/Ask Spread: Tighter is better—wide spreads signal poor pricing efficiency

- Volume: Tells you how actively the contract is being traded

- Open Interest: Shows how many contracts are currently open—higher = better fills

🚩 Always use a limit order when placing a covered call trade.

Covered Calls and Implied Volatility

Options traders have an obsessive relationship with implied volatility (IV). In particular, they love selling options when IV is high—and that’s exactly what you should be looking for when selecting your short call.

.png)

High IV means richer premiums, but it also implies a lack of price stability, which can make for huge swing on the stock side.

Covered Calls and Time Decay

Covered call traders love time decay. It’s a key reason this trade exists. In a stable environment—meaning the stock price and implied volatility don’t move much—the value of your short call option steadily drops. That decay works in your favor.

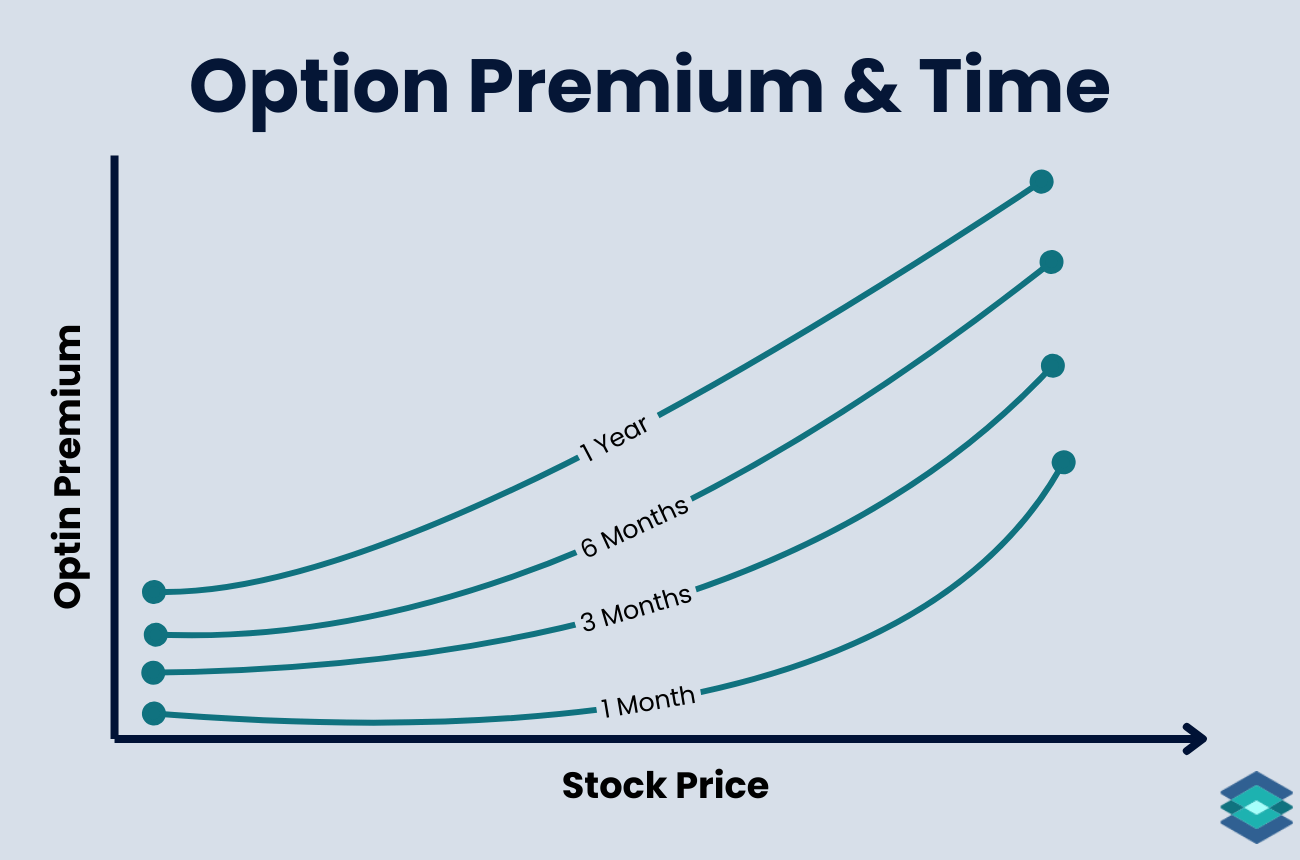

It’s very important to know that time decay isn’t linear. If you sell a call with a year until expiration, it barely loses value day to day. Same with six months out. But once you hit around 45 days to expiration, that’s when theta really kicks in and the decay starts to pick up speed.

.png)

Covered Calls and The Greeks

In options trading, the Greeks are a series of risk management tools that hint at the future price of an option based on changes in different variables. Here are the 5 most important Greeks to know:

- Delta – Measures how much the option price moves relative to the underlying stock.

- Gamma – Tracks how Delta changes as the stock moves.

- Theta – Measures time decay, showing how much value the option loses daily.

- Vega – Sensitivity to implied volatility, affecting option price.

- Rho – Measures impact of interest rate changes on the option price.

And here is the relationship between naked short puts and these Greeks:

Managing a Covered Call

Options trading isn’t passive investing. If the short call in your covered call is sitting in that ideal 30–45 DTE window, you’ll need to stay on top of it. This trade takes active management.

Unless, of course, your goal is to sell the stock at the strike price. In that case, assignment might be part of the plan.

But if your goal is to hold onto the stock, it’s going to take some work.

Rolling to Avoid Assignment

If the stock starts creeping toward your strike, and you want to keep your shares, consider rolling the call. Rolling can:

- Push the strike higher (more upside)

- Extend time (more theta decay)

When you roll to a further out strike price, this can be done in a vertical spread trade. When you roll to a different month, this is called a calendar spread. When you do both at the same time, it’s called a four-leg roll.

When to Close It Early

As option expiration approaches and your short call remains safely out of the money, chances are it’ll be trading for just a few pennies in the final days or week. At that point, you’ve likely captured 95% or more of your profit potential. It might make sense to close the position and roll it to a new expiration.

As we mentioned earlier, time decay picks up around the 45 DTE mark, so consider targeting that range when reestablishing the trade via a calendar spread.

Covered Call Calculator

Want to visualize how a covered call pays off under different conditions and timeframes? Check out our Covered Call Calculator below!

⚠️ Covered calls involve risk, particularly if the underlying stock declines in value. While the premium received offers some downside cushion, losses can still be significant. This strategy may not be suitable for all investors and should only be used with a full understanding of the risks. Commissions, fees, and taxes are not reflected in and may affect returns. Read The Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before trading options.

FAQ

A covered call works by buying 100 shares of stock and selling a call option, typically out of the money. If the stock price remains below the strike price of the sold call on option expiration, you keep the full premium from the option sale.

Yes—you can lose a lot of money on the stock side of a covered call. The credit you receive from the short call only offers limited downside protection. If the stock drops a lot, that small premium won’t offset the loss.

Covered calls can be considered “bad” in certain situations because the short call option limits your stock’s upside potential.

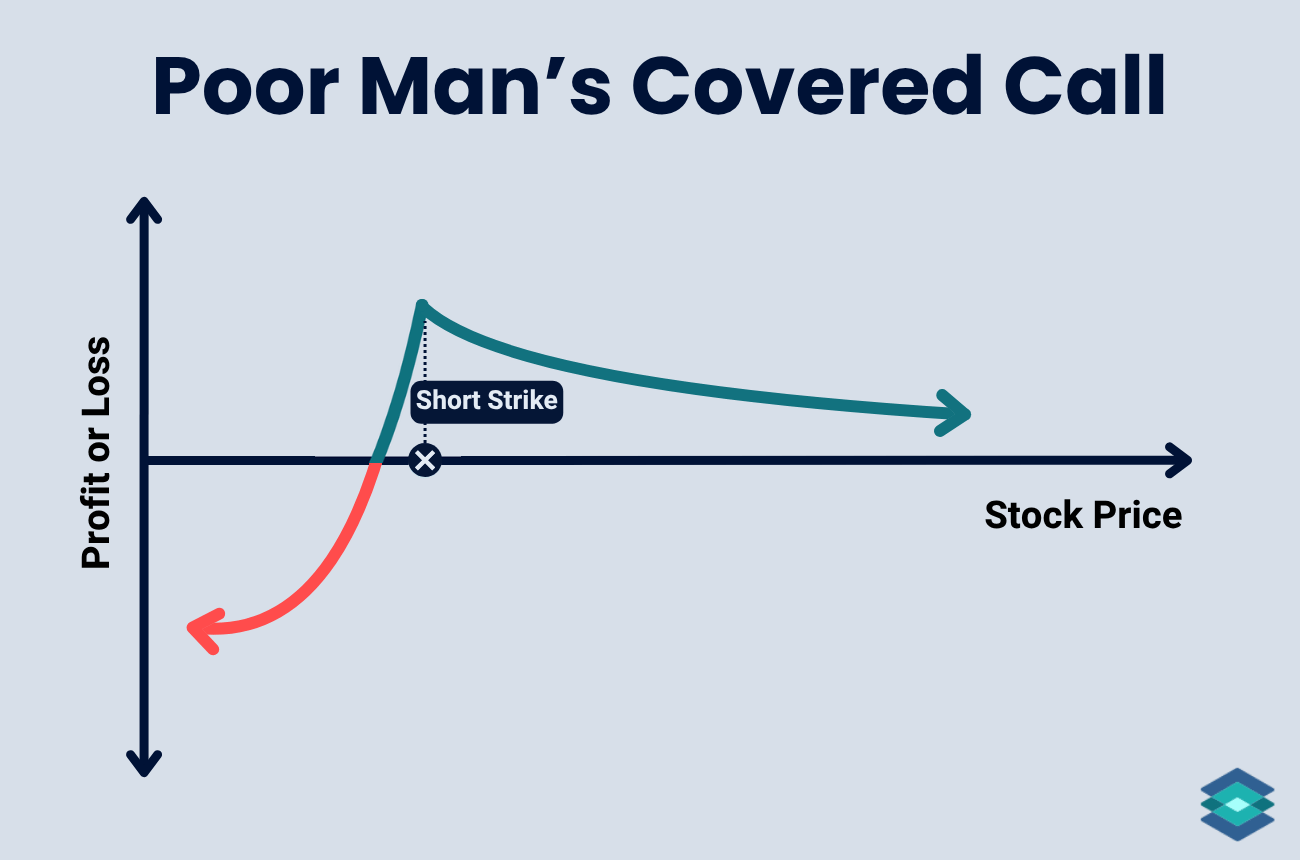

A poor man's covered call consists of buying a long-term in-the-money call option (LEAPS) instead of owning the stock and selling a shorter-term out of the money call against it. This reduces capital requirements while mimicking a covered call strategy.

The most you can lose is the stock purchase price minus the premium received.

If you buy the stock at $100 and sell a call for $1, your max loss is $99 per share. That happens if the stock drops to zero—you keep the $1, but the stock is worthless.

You may get assigned on the call portion of your covered call if the short call option goes in the money—meaning the stock price rises above your strike. This early assignment risk increases as expiration approaches.