Diagonal Spread Options Strategy: Beginner's Guide

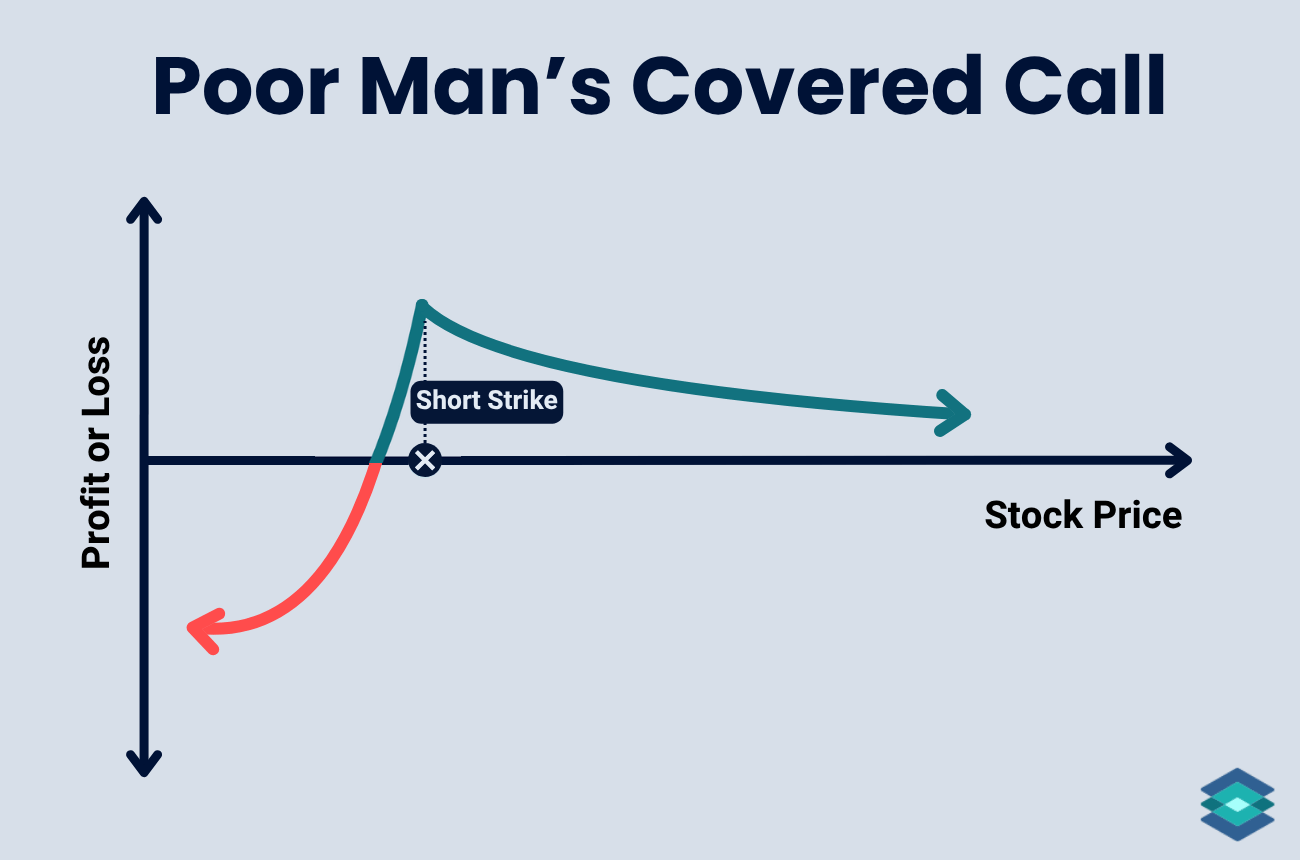

The diagonal spread involves buying an in the money option in a later expiration cycle and selling an out of the money option in a nearer cycle. The trade is, therefore, part vertical and part calendar. It takes a directional view on the underlying asset while adding a time component.

You can buy or sell diagonals, but since long diagonal spreads are the most common and favored by traders, we’ll focus on the long version. The most you can lose on a long diagonal is the debit paid (not counting assignment risk), while profit is open-ended because the long option’s value at the short’s expiration can’t be known in advance.

Highlights

- Risk: Losses are capped at the debit paid, with assignment risk as the main factor to monitor.

- Reward: Upside is open-ended, since the long option can hold time and volatility value after the short expires.

- Outlook: Works best when you have a directional view and expect the stock to drift toward your short strike.

- Efficiency: The short leg reduces entry cost, making diagonals cheaper and more flexible than buying a single option.

- Sweet Spot: Peak performance comes when the stock finishes near the short strike at expiration.

- Implied Volatility: Slightly positive exposure, as the long leg benefits from rising IV while the short offsets some of the gain.

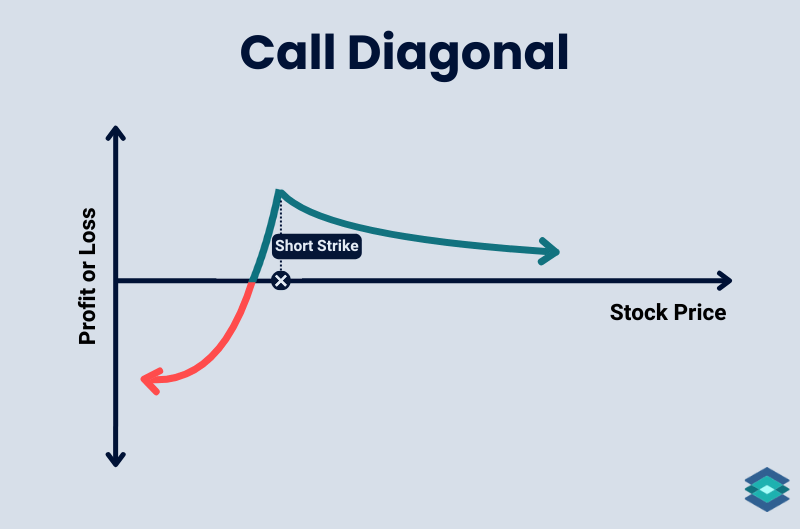

Call vs Put Diagonal

Diagonal spreads do not really change between calls and puts. The only difference is which way we want to lean.

- With a call diagonal, we’re bullish. We buy a longer-dated ITM call for staying power and sell a nearer-term OTM call to cheapen the trade and let decay work for us.

- With a put diagonal, we’re bearish. We buy time with the long ITM put and sell a nearer-term OTM put to bring in option premium while leaning to the downside.

In both cases, risk is capped at what we pay, and the sweet spot sits around the short strike. The only choice is whether we want to lean up or down.

Diagonal Trade Components

The diagonal is a two-legged trade:

- The long option is the anchor. Buy it farther out in time, usually slightly in the money, so it holds value and gives staying power.

- The short option is the income piece. Sell it closer to option expiration, usually out of the money, to collect premium and take advantage of faster decay.

The long provides time, the short provides income. Whether built with calls or puts, risk stays capped at the debit we pay.

Diagonal Spread: Call Payoff Profile

Let’s now look at the max profit, loss, and breakeven for a diagonal trade.

Max Profit Zone

With a diagonal, profit isn’t capped the way it is with verticals. The sweet spot comes when the stock finishes near the short strike at expiration. The short expires worthless, while the long still carries time value. Because the long call value depends on implied volatility and time, the maximum profit is undefined.

Let’s say ABC is trading around $100, and we want to set up a diagonal call spread. We’ll buy a slightly in the money option with more time and sell an out of the money option in a nearer cycle:

- Long Call Strike: 98 (Mar) @ 4.50

- Short Call Strike: 102 (Feb) @ 2.00

- Net Debit Paid: $2.50

- Max Loss: $250 (the debit paid)

- Peak Profit Zone: Around the 102 short strike

As expiration approaches, the trade performs best if ABC drifts into the short strike. That’s where decay helps the short leg while the long retains value, creating the ‘max profit zone’, as seen below:

Max Loss Zone

The most you can lose on a diagonal is the debit you pay up front. That happens if both legs lose value and expire worthless. Risk stays capped, no matter how wrong you are on direction.

Returning to our ABC trade, we can see the risk is fixed at $250, the cost of entering the spread. No matter how low the stock goes, the loss cannot exceed that debit:

- Net Debit Paid: $2.50

- Max Loss: $250

It’s worth noting that unless the stock makes an extreme move, there will usually be some extrinsic value left in your long option, depending on how much time remains until expiration.

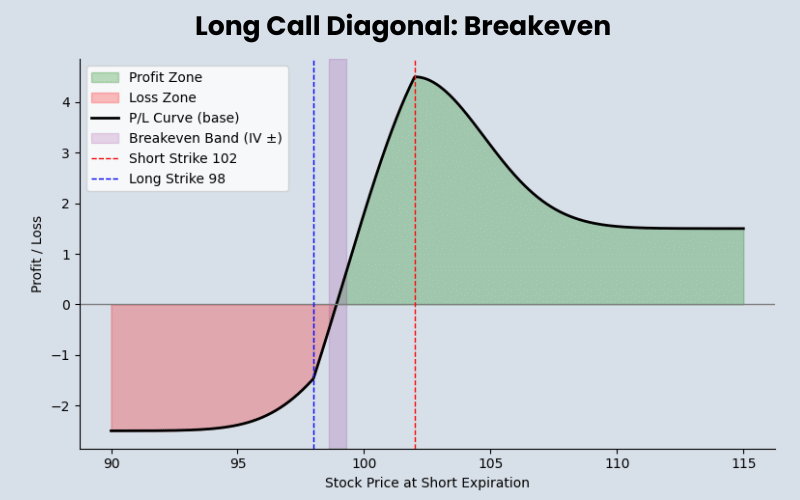

Breakeven Zone

Breakeven on a diagonal comes from the net debit, but it isn’t a fixed number. It depends on the value of your long option when the short expires, including any remaining time value.

In our ABC trade:

- Long 98 Mar Call @ 4.50

- Short 102 Feb Call @ 2.00

- Net Debit Paid: 2.50

If ABC finishes near $99 at the Feb expiration, the long 98 Mar call is $1 in the money. Add the time value it still carries (which changes with IV), and you’re close to covering the 2.50 debit. Of course, this is dependent upon IV, which we didn’t include. That’s why breakeven shows up as a band just under $100 in our example below.

Diagonal Spread: Put Payoff Profile

Let’s now briefly cover what this looks like for a put spread. The structure is the same as the call diagonal, just flip everything horizontally.

We buy a longer-dated ITM put and sell a nearer-term OTM put. Risk is capped at the debit, profit peaks near the short strike, and breakeven changes with the long option’s remaining time value.

Example with ABC at $100:

- Long 102 Mar Put @ 4.50

- Short 98 Feb Put @ 2.00

- Net Debit Paid: 2.50

- Max Loss: $250 (the debit paid)

- Peak Profit Zone: Around the 98 short strike

We can see the put payoff zones below:

Outlook: When to Buy a Diagonal Spread

Here are a few situations where the trade makes sense:

- Directional With a Target: When you expect a stock to move toward a certain level but not rip through it, the diagonal gives you defined risk and rewards you for being right on direction and timing.

- Rising Implied Volatility: Buying more time while selling shorter premium helps if IV increases. The long option holds value while the short decays.

- Cost-Efficient Alternative: Compared to buying a single long option, the short leg reduces entry cost and makes diagonals a flexible way to express a view.

Margin Requirements

The long diagonal is a defined-risk debit trade. Margin requirements are straightforward. You only need to post the net debit you pay to enter the position, plus commissions and fees.

- Margin Requirement = Net Debit Paid

Because risk is capped at the debit, brokers do not require additional margin. This makes the long diagonal capital efficient compared to outright long options, since the short leg helps offset cost while keeping maximum loss defined.

Real World Diagonal Trade Example

In this example, we’re going to buy a diagonal spread on XLF (Financial Select Sector SPDR Fund).

The Fed will be meeting soon to decide interest rates, and financials are likely to react. We’re taking a long-term bullish stance on financials, but in the near term, we’ll sell a call to reduce our cost basis.

Let’s head over to the TradingBlock XLF options chain to find our expirations and strike prices.

So we’re paying $0.90 for a 1.5 point spread. That works out to about 60% of the width, which keeps the trade efficient and well under our 75% guideline. Risk is capped at the debit, and the sweet spot lines up around the short call at the 54.5 strike.

Let’s now send the trade off to get filled. Remember, always try the midpoint first. If you don’t get filled, work the order up in penny or nickel increments. Read more about options liquidity here.

XLF Diagonal: Trade Details

And here are the details of the trade we just put on:

- Current XLF Price: $53.11

- Buy 53 Call (Oct 17, 37 days to expiration) @ $1.15

- Sell 54.5 Call (Oct 3, 23 days to expiration) @ $0.25

- Net Debit Paid: $0.90 ($90 total)

And here is the payoff profile:

- Breakeven Zone: Sits just under $53 at the short expiration

- Max Profit: Undefined (depends on value of long call after short expires)

- Max Loss: Debit paid = $0.90 ($90 total)

- Profit Range: Sweet spot near $54.50 at Oct 3 expiration

- Risk/Reward: Risking $90 with potential upside open as long as the long call retains value

Let’s now explore a few trade outcomes!

XLF Diagonal: Winning Trade Outcome

Twenty-three days have passed, and our short expiration is upon us. After a little volatility, XLF settled nicely near our short strike price:

- XLF Price: $53.11 → $54.70 📈

- Expiration: 23 days → 0 (short leg expires)

- Buy 53 Call (Oct 17) @ $1.15 → $1.88

- Sell 54.5 Call (Oct 3) @ $0.25 → $0.20 (intrinsic value)

- Final Spread Value: $1.68

- Net P/L: +$0.78 ($78 total) ✅

Let’s now see out this trade played out in real-time.

XLF Winning Diagonal: Under the Hood

.png)

Note that the short 54.5 call had $0.20 in intrinsic value on expiration because XLF finished at $54.70. Since we sold the option for $0.25, we only made $0.05 on the short leg.

The real driver of the profit was the long 53 call. When the short expired, this option still had 14 days left, which means it still contained a lot of extrinsic value (time+implied volatility). That carryover of premium is what makes diagonals so effective when the stock drifts toward the short strike.

In the real world, the 54.5 short call would have been assigned, leaving us short 100 shares of XLF the next trading day. Since we’re still long the in the money 53 call, we could either buy back the stock and sell the call as a covered call or just exercise the long call to neutralize the position.

XLF Diagonal: Losing Trade Outcome

In this trade outcome, XLF sold off hard and finished expiration day below both strike prices.

- XLF Price: $53.11 → $52.00 📉

- Expiration: 23 days → 0 (short leg expires)

- Buy 53 Call (Oct 17) @ $0.90 → $0.21

- Sell 54.5 Call (Oct 3) @ $0.00 → $0.00

- Final Spread Value: $0.21

- Net P/L: –$0.69 (–$69 total) ❌

Our short expired worthless, but our long fell right with it, closing at 0.21 on short expiration. That reduced our loss, leaving us with a net loss of $0.69 ($69 total) compared to the original debit of $0.90.

XLF Losing Diagonal: Under the Hood

.png)

This was a bad outcome, but not the worst-case scenario. Because our long call still had 14 DTE when the short expired, we were able to recover some extrinsic value, closing it at 0.21. Our max loss would have been the full debit paid, but salvaging that long call reduced the hit to about 77% of max loss.

It’s worth noting that at 11 DTE, our diagonal spread was trading at $1.54, about 70% higher than our initial debit of $0.90. Closing the position there would have locked in a solid profit before the underlying rolled over. I prefer to use GTC limit orders to take profits on spreads.

Managing Diagonal Spreads

Diagonal spreads have a lot of moving parts. If you’re trading European-style options like SPX or NDX, you’ll face fewer complications. But with American-style options (stocks and ETFs), you’re exposed to early assignment risk, dividend risk, and pin risk, among others. Here are a few ways to manage diagonals effectively:

- Roll the Short Leg: If your long option has plenty of time left, you can continuously roll the short option forward. This turns the diagonal into more of an income generation strategy, collecting premium while keeping the long as the anchor.

- Assignment Risk: Be mindful if your short option goes deep in the money. Early assignment can occur, especially around dividends. Rolling early can help you avoid unwanted stock delivery.

- Dividend Risk: Short calls on dividend-paying stocks are at higher risk of assignment right before the ex-dividend date. Know your stock’s dividend schedule.

- Pin Risk: If the underlying finishes close to your short strike at expiration, you may not know until after the close whether you’re assigned. Closing or rolling ahead of expiration reduces this risk.

Choosing Your Strikes & Delta

Choosing the right strike prices is crucial to a diagonal’s success. It helps to first understand delta.

In options trading, delta is the option Greek that refers to how much an option's value may change given a $1 move up or down in the underlying asset. Delta also tells us:

- The number of shares an option ‘trades like’

- The probability that an option has of expiring in the money

Choosing the Long Option

At the money options have a delta of around 0.50, meaning there is a 50% chance they will expire in the money (negative for puts). For the long leg, I like to target a strike with a delta in the 0.55 to 0.65 range.

We can see this range below on TradingBlock for SPX call options:

Being slightly in the money gives the option staying power, since it carries some intrinsic value and won’t bleed out as fast as an out of the money contract.

Choosing the Short Option

For the short leg, I’ll typically look for a delta in the 0.20 to 0.35 range. This is a bit higher than my usual short delta target of 0.15 to 0.25, because with a diagonal, I actually want the underlying to finish near the short strike.

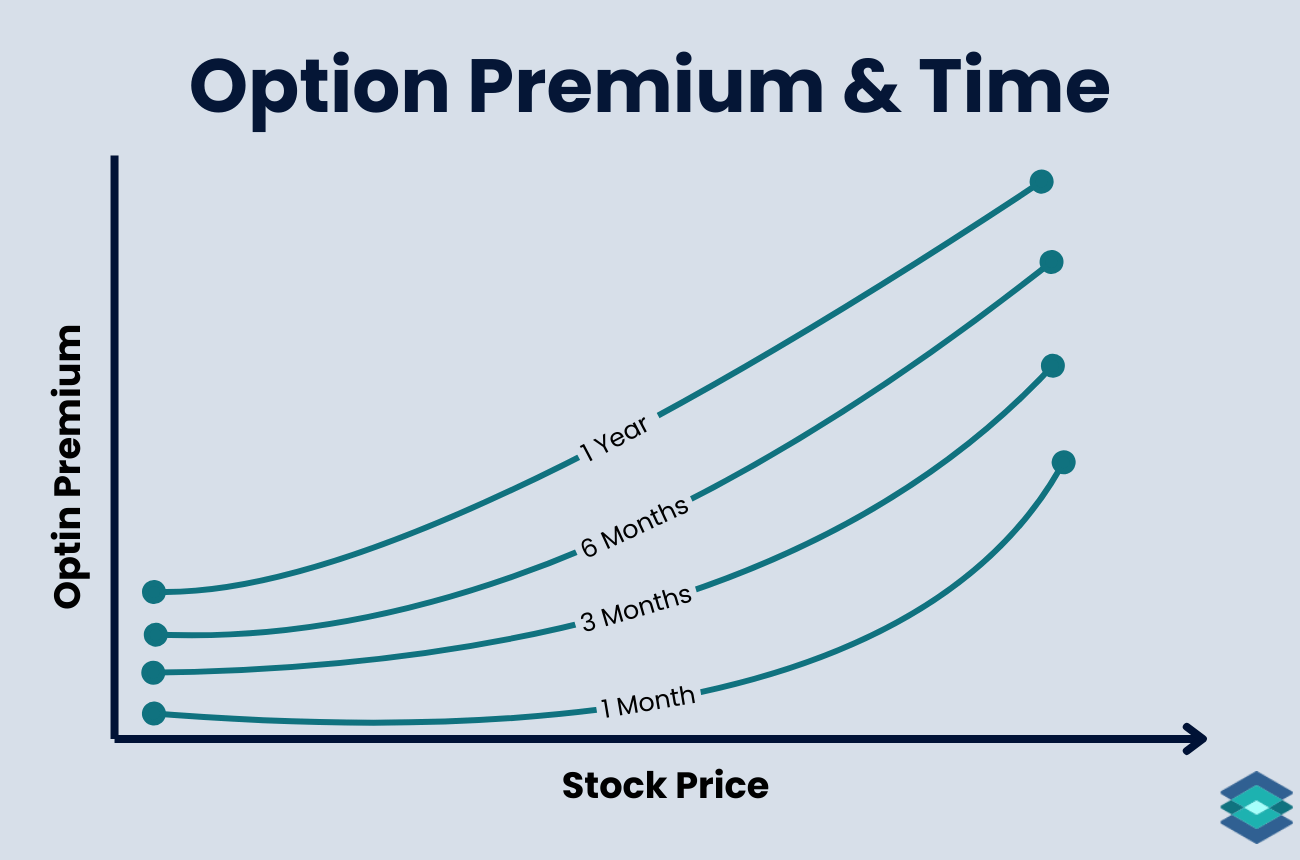

Time Decay and Theta

Theta is the option Greek that tells us how much an option is predicted to lose in value each day, assuming price and implied volatility stay the same. Theta is the reason that we are short an option in the diagonal spread.

Each day that passes without a big move in price or volatility allows you to keep more of the premium collected from the short option. The pace of this decay speeds up as expiration gets closer, which is why diagonals are often built with short options expiring in this acceleration window.

.png)

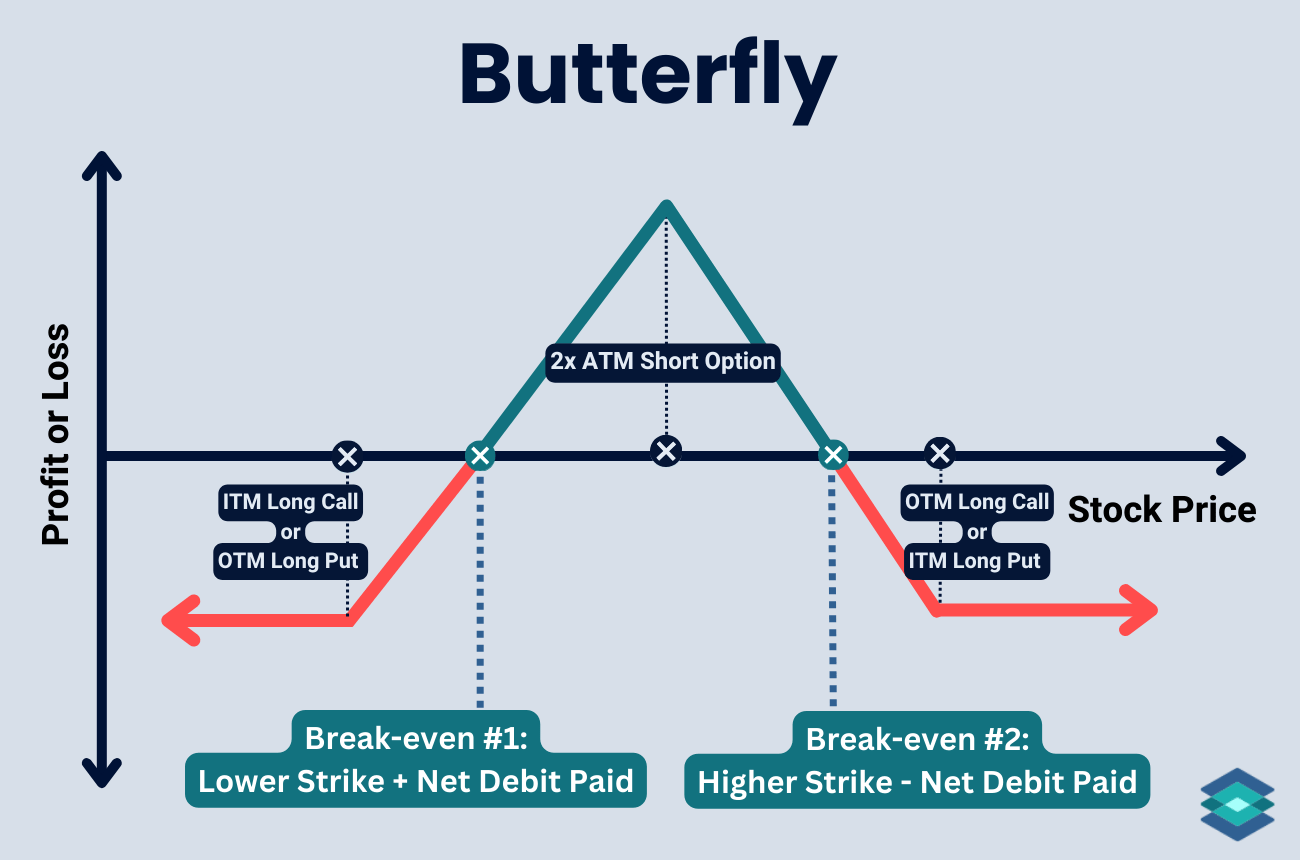

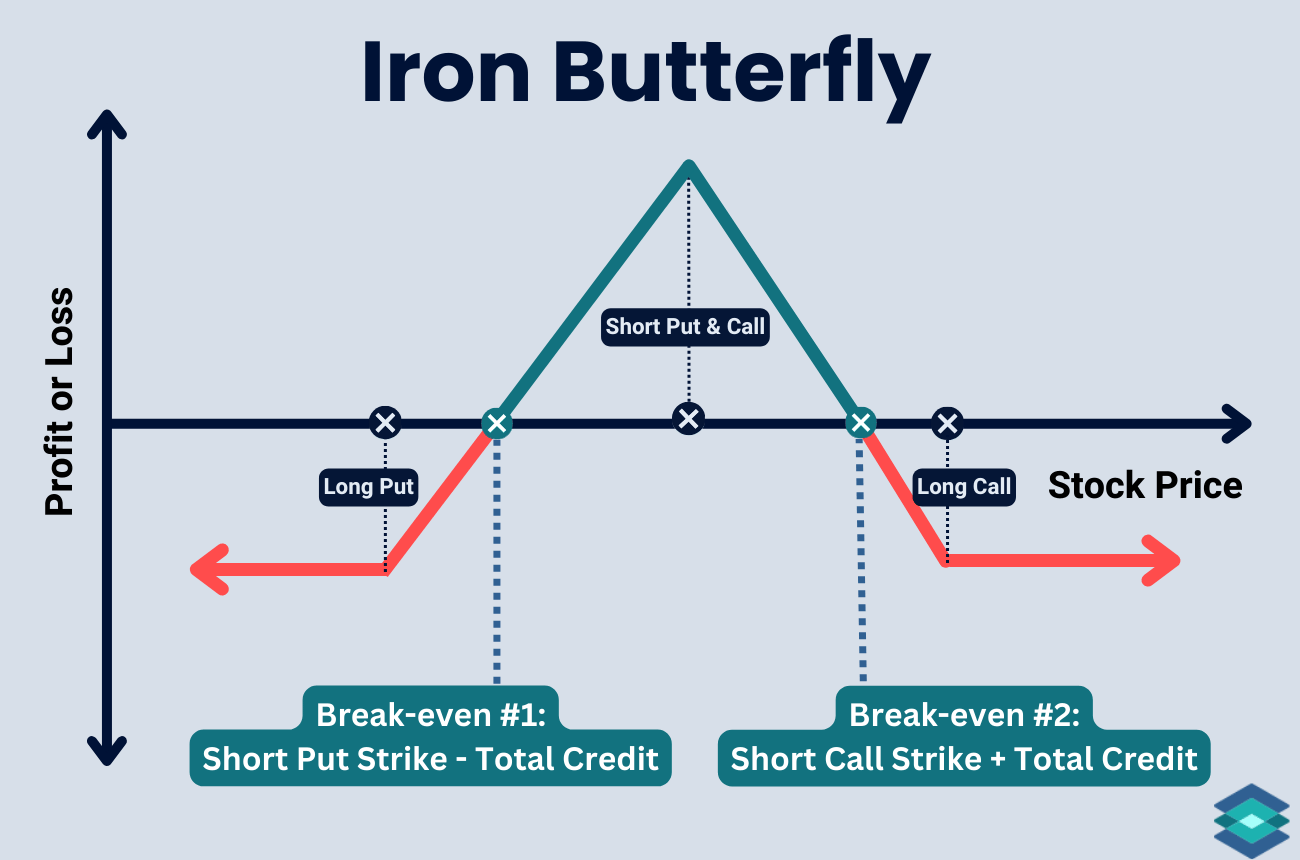

Diagonal vs Vertical vs Calendar Spread

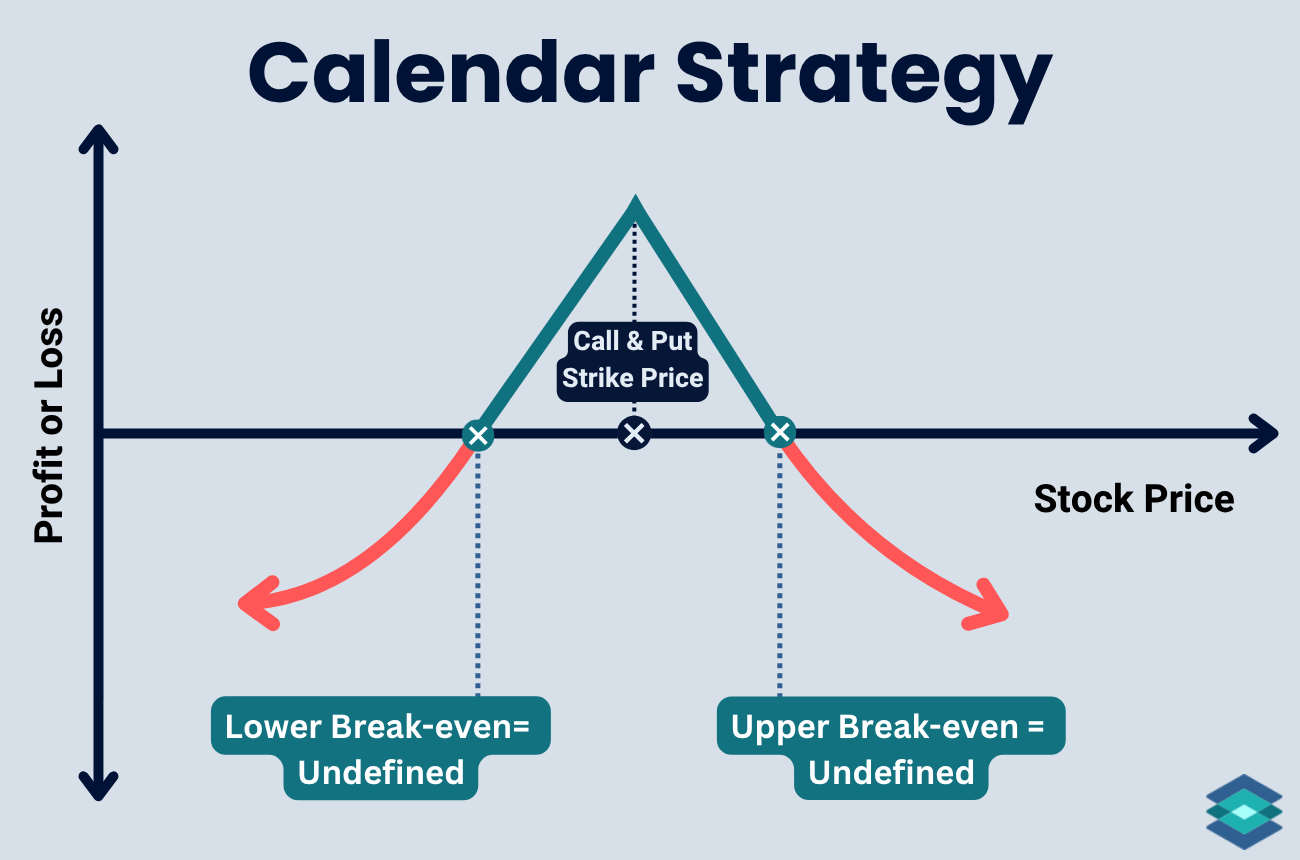

A diagonal spread includes elements of both the calendar (time spread) and vertical spread.

Vertical Spread

- Same expiration

- Different strikes

Calendar Spread

- Same strike

- Different expirations

Diagonal Spread

- Different strikes

- Different expirations

We can see a visual of these three spreads strike setups below:

.png)

Diagonal Spreads and The Greeks

In options trading, the Greeks are a set of risk metrics that help estimate how an option’s price will respond to changes in key market variables. Here are the five most important Greeks to know:

- Delta – shows how much an option price changes for a $1 move in the stock.

- Gamma – shows how much delta shifts when the stock moves $1.

- Theta – shows how much an option loses value each day from time decay.

- Vega – shows how much an option price changes for a 1% change in implied volatility.

- Rho – shows how much the option price changes for a 1% change in interest rates.

And here is the relationship between long diagonals and these Greeks:

⚠️ This strategy may not be suitable for all investors. Results can also be affected by assignment risk, commissions, fees, and slippage, which are not reflected in the examples. Always read The Characteristics and Risks of Standardized Options before trading

FAQ

A diagonal spread is part vertical, part calendar. It uses different strikes and different expirations to create a defined-risk trade with flexibility.

They can be if the stock drifts toward your short strike while the long leg retains value. Profit peaks around the short strike, though outcomes vary with IV and timing.

Call diagonals are bullish, leaning into upside moves. Put diagonals are bearish, leaning into downside moves.

No, long diagonals are typically debit spreads. You pay a net debit up front and risk is capped at that amount (not counting assignment risk and fees/slippage).

Buy a longer-dated ITM option for staying power and sell a nearer-term OTM option for income.

This creates the balance of time and direction.

Verticals use different strikes but the same expiration. Diagonals use different strikes and different expirations.

Calendars use the same strike with different expirations. Diagonals add a strike difference on top of the time difference.